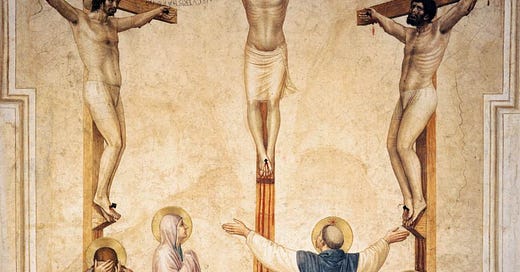

The Gospel story about that criminal crucified next to Jesus, who entered Paradise that same day, tells you the karma concept in its erroneous modern interpretation is a delusion. No one gets what they deserve, in both good and bad senses.

From the days of our childhood, we hear fairytales where good and kind heroes trump villains in the end, and justice is always restored there. In life, yet, it is often exactly the opposite, at least from a human perspective.

The righteous do perish in their righteousness, as the wicked live long, eat well and get a state funeral in the end.

Ecclesiastes 7:15, Twitter Revised Edition

I believe a part of the good life is to accept this reality and spare yourself from the sometimes devastating urges of revenge, envy, and jealousy.

Let’s consider some concepts that may drive the modern man into this misery, when everything may feel unbearably unjust.

Karma.

I rely on Alan Watts in this one. In several of his works, he described in detail why karma (and samsara, for that matter) is greatly misunderstood in the West and often taken in their most vulgar interpretation.

According to Watts, karma is “an action which always requires the necessity for further action. When the solution of a problem creates still more problems to be solved, when the control of one thing creates the need to control several others.” I’m amazed at how well this describes the life of the modern man, with all the attempts at its ‘optimization’, and how far it is from the concept: “Joe was a bad guy, he will turn into a pig in his next incarnation.”

The vast majority of Asian Hindus and Buddhists continue to believe that reincarnation is a fact. [...] Western Buddhists even find this belief consoling, in flat contradiction to the avowed objective of attaining release from rebirth.

Alan Watts, Psychotherapy East & West

So, when you find out that the future never comes, and the past does not exist, you’ll get the point that now is somehow the definition of eternal life. As Jesus said, “Before Abraham was, I AM.” When you realize this, the consequent vicious circles of samsara will vanish, and that “flaming sword” in the hands of the cherubim will stop rotating (Gen 3:24), and the Garden gates will be free to pass through again.

God and Justice

Here’s another point from our naïve youth: “If God exists, why doesn’t He punish all the bad guys?” This hits so hard sometimes that we start thinking it might be better to take the dark side—or at least to believe the Earth is nothing more than a meaningless, hostile place hosting bio-parasites. Indeed, if you look around, you cannot deny that everything happening is far, far from fair: horrific atrocities of war and diseases are still present, even in the most civilized places like Europe.

Does this mean that God cannot, or does not want to, extend His justice to the creature? Not at all. “The judgments of God are sometimes hidden, but they are never unjust.” — paraphrased from Augustine.

Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!

Romans 11:33 (ESV)

Yet, time and again, we hear people express hope that eventually, at least after death, God will “bring the bad guys to justice.”

The problem is that this idea of “justice” comes from a human perspective, not God's. What happened with Rebekah and Jacob deceiving Isaac and Esau (Genesis 25–27) wasn’t fair by human standards, but it was acceptable within God's inscrutable plan. What happened to the criminal crucified next to Jesus wasn’t fair either. Was it just, what happened to Saul, also known as St. Paul?

The fairness and moral clarity we often expect from God is a chimera, a fantasy sharpened by cheap movies like John Wick.

A modern myth of moral clarity goes like this: the hero suffers injustice, the hero fights back, justice is restored through violence. In contrast, God’s justice in Scripture often appears unfair, slow, inscrutable, or even merciful to the “wrong” people, like Nineveh in Jonah 3–4, or Saul being forgiven.

Divine justice in the Bible is often unpredictable, patient, and radically merciful. It is not personal, violent, or emotionally satisfying, as modern media often portrays it. Well, violent too, of course.

One of the most paradoxical themes of Christianity is that men cannot justify themselves by their deeds: “Abraham believed God, and it was accounted to him for righteousness.” (Romans 4:3) And exactly because of that, “Lord rewards not for the effort, but humility” as St. Isaac the Syrian said. Orthodox Church Fathers used to say that the goal of a Christian life should be acquiring the grace of the Holy Spirit, which is a hard task by itself. And yet, it cannot be earned, as it is given for free.

The Book of Job

If you read the Book of Job, it becomes clear that one should be prepared to lose everything for no apparent reason. Yet for Job, all he lost was eventually restored. My reading of this is that a bond is acceptable. "Walk in the ways of your heart" (Ecclesiastes 11:9). But don't cling.

Job did not suffer because of anything he had done. Often, our "irrational" fate must simply be accepted, because we do not know the full play. Who else suffered not because of his deeds? And what is the only way you can truly see God? “I have heard of You by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees You.”

The Book of Job tells us that it is, in fact, fine to be irrational. Another non-obvious outcome is that Job becomes a reflection of Christ. That, perhaps, is his greatest reward: he sees the Savior—possibly before anyone else on Earth.

The Prodigal Son must return.

Injustice exists only within human society, in Nature, there is no injustice. I believe humans suffer because they left Eden, having been free, and they forgot that He called them gods (John 10:34). As a result, their nature inherited the consequences of missing the point, i.e. the sin.

Yet the Prodigal Son must return. That’s the only hope, because you cannot force your children to love you.

What is fair for God is not necessarily fair for people. The Prodigal Son is coming back, again and again, forever and ever—and he is always accepted. It is always considered fair in the eyes of the Father, because this is what everyone deserves: to return to the Garden.